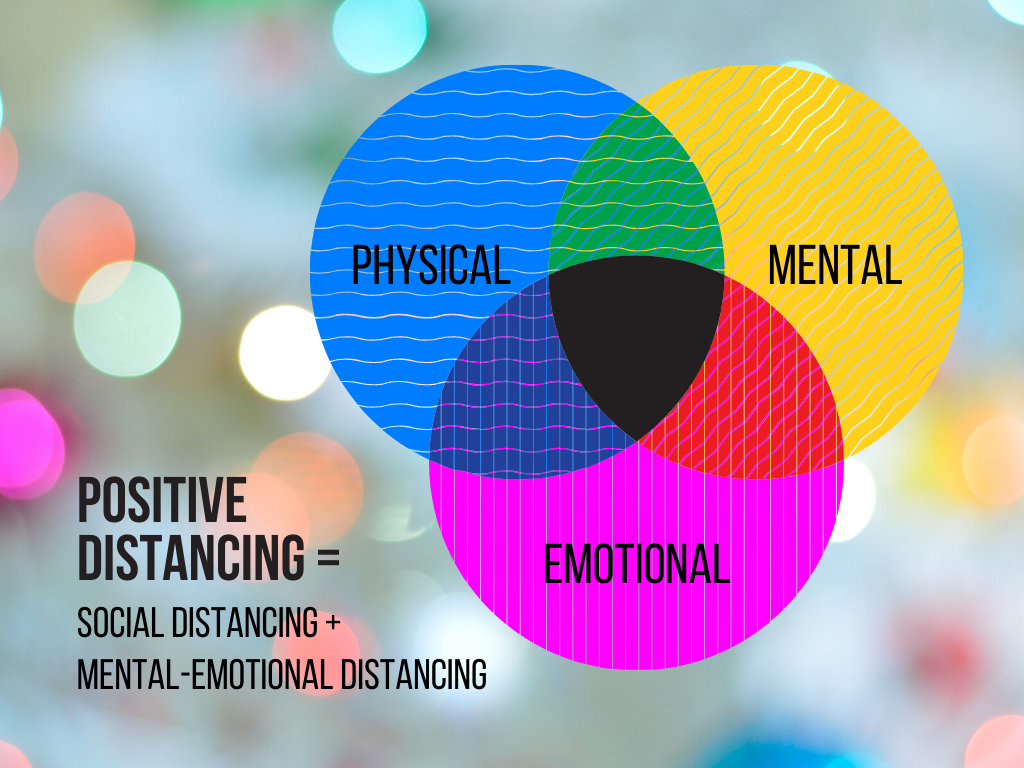

Positive Distancing: Combining Social Distancing and

Mental-Emotional Distancing

Jun Kabigting, MBA/MSIE/SPHRi

This article is part of a series of articles from the author on the central concepts and principles of Positive Psychology, the scientific study of what goes right in life (Peterson, 2006), which is the science behind the #PositiveHR framework.

The world is in lockdown. Stock markets are melting down. The economy is in free fall. People are panic buying. Schools, pubs, restaurants, and other public places we take for granted are shut. And the saddest reality of it all, people are dying.

With all of these happening at such a rapid pace, people will naturally experience cognitive overload and dissonance. Amidst all this chaos, uncertainty and anxieties, how can people and organizations help prevent and contain the spread of this latest nemesis that is Covid-19 or simply, the Coronavirus, and at the same time, keep our sanity to survive and thrive under these trying times?

Social Distancing: Public Health and Epidemiology

First, let's discuss how we can help contain the spread of the virus. By now, the term social distancing has become a household word and has been the de facto action of governments worldwide. The term itself came from one of the cornerstones of public health known as epidemiology (the study and analysis of the patterns and risk factors or determinants of health and disease conditions in a given population; Porta & IEA, 2008). Briefly, social distancing is a preventative public health measure intended to slow down, if not stop, the transmission of a contagious disease or pathogen such as Covid-19 (Johnson, Sun, & Freedman, 2020). This is why governments have suspended schools, closed down borders and airports, and put countries under a state of emergency or disaster; sports associations are postponing sporting events; event organizers canceling conferences, shows and concerts; companies temporarily closing down businesses; and, people staying at home.

The objective of these draconian measures is to simply break the possible chains of transmission of the virus from an infected person to a healthy one so that a country's healthcare system doesn't get overwhelmed by the exponential influx of people infected by the virus. This is called "flattening the epidemic curve," which keeps medical providers from being overburdened and also helps buy some time to develop a treatment (preferably a vaccine) soon (Specktor, 2020). Statistically speaking, we want a platykurtic or flat distribution (i.e., the height of the curve is below the capacity level of the healthcare system) rather than a leptokurtic or thin distribution (i.e., the height of the curve exceeds the capacity level of the healthcare system).

Image source: Center for Disease Control (CDC)

So far, these measures, as drastic as they are, seem to be working as experienced by China and South Korea, the original epicenters of the pandemic. However, there are some unintended consequences of social distancing, such as loneliness, isolation, lower productivity, loss or reduced human interaction and one's psychological well-being. It's like having cancer where your only choice is to undergo chemotherapy, which can have some severe side effects. Social distancing is indeed a bitter pill to swallow.

Mental-Emotional Distancing

To counteract the adverse effects of social distancing, the use of mental-emotional distancing strategies can be useful to reduce cognitive overload (mental exhaustion) and emotional drain with the aim of helping build psychological resources that people can use to overcome crises or traumatic events. In the current context, mental distancing is the intentional avoidance of thinking about the virus and, by doing so, provides a person some rest (i.e., emotional distancing) from over-worrying or anxiety about the effects of the virus (Brower, 2020).

So, what strategies one can use in enacting mental-emotional distancing? From the mental distancing aspect, you can do the following (Brower, 2020):

-

Take a break from traditional and social media. In short, don't listen, watch or read the news, especially about the virus for at least an hour. Digitally detoxify. Turn off the TV or log out from your social media accounts.

Designate free zones. That is, identify a specific part of your house or office that no discussions about the virus are permitted. Discuss something else other than the virus.

If you can't do #2, set boundary conditions. Whenever you do meet or discuss with family members, friends or colleagues, let them know that anything related to the virus is off the table for discussion. Just like in Harry Potter, it is a word that can never be uttered. For fun, you can even set a fine for someone who brought the topic about the virus.

Get physical. Even though most public gyms are closed, you can still do some light to moderate home exercises such as stretching, yoga, strength training, or if you are up to it, pump some muscles with your dumbbells or weights. Ride on your treadmill, Peloton or running machine if you have one. If you prefer dancing, watch Zumba, Hip-Hop or high-intensity interval training (HIIT) exercises on YouTube for free. Be creative, resourceful, and don't make excuses. Our body is biologically designed for movement, so move that body and let go of some sweat.

Get some fresh air. If you are living in a place where there is no complete lockdown, take advantage of it by going out for a jog, walking out your pets or babies, or just breathe some fresh air. You are not in prison, so as long as it is safe to step outside, explore your neighborhood but do maintain the 6-feet recommended physical distance with another person. And after you come back from outside, wash your hands for at least 20 seconds and gargle your mouth to clean your mouth with other bacteria that may weaken your immune system (i.e., gargling DOES NOT kill Covid-19).

What is important to note is that if you want to take a break from everything related to the virus mentally, physical movement is a great way to do that. By doing so, you shift your attention away from processing mentally exhausting information to physical activities, which may be physically exhausting, but gives you mental breaks. As Csiksentmihalyi (1990) once said, attention is our most important tool in improving the quality of our experience. In short, whatever you give attention to gets amplified.

Positive Psychology Interventions for Mental-Emotional DistancingThe science of positive psychology can also offer several interventions that can be useful in practicing mental-emotional distancing.

-

Benefit finding. This refers to a reported positive life change resulting from the struggle to cope with a challenging life event such as trauma, illness or other negative experiences by enhancing emotional and physical adaptation in the face of adversity (Riley, 2013). Because of office closures, you may not be able to work at the office, but instead, you can work virtually at the comfort of your home and even in your pajamas. Better yet, you don't have to drive to the office and get stuck in traffic. You also saved on gas! In short, count your blessings rather than your misses.

-

Cognitive reappraisal/reframing. This is an emotion regulation strategy that is useful when the stressful situation at hand cannot be changed, just like the current pandemic. It involves lessening the emotional impact of a stressful situation by reframing or reappraising the initial perception of it (Gross & John, 2003). For example, social distancing from other people may have isolated you from others, but you can view the situation as an opportunity for you to develop closer ties with your immediate family or loved ones since you are "forced" to spend more time with them, which in normal circumstances may not be the case. Who knows, you might find out something new about your significant other that may reignite your stalled relationship.

Mindfulness. This is the practice of being able to tune in to what’s going on in one’s mind and body and in the outside world, moment by moment (Teasdale, Williams, & Segal, 2014). Mindfulness is one of the many techniques used in the evolving art and science of meditation, considered as one of the most enduring, widespread, and researched of all psychotherapeutic methods (Walsh & Shapiro, 2006). The good news is that there are already many virtual and physical resources out there to do this. Google "mindfulness," and you'll most likely find a mindfulness technique that fits your needs and preferences.

Savoring. It is the awareness of pleasure and deliberate attempts to make it last (Bryant & Veroff, 2007) and is considered as the positive counterpart of coping (Peterson, 2006). In other words, it is the intentional prolonging of the experience of something pleasurable. One way to do this is to savor the experience of eating a home-cooked meal matched with your favorite wine or drink. Notice the color, texture, smell, temperature, taste, presentation, table arrangement and even the ambiance of your dining room. In our everyday routine, we take these things for granted, but now that we are forced to slow down, we can spend some time to savor these small things and appreciate and be grateful for the things we have.

Elevation. In times of crises and emergencies, we see people exhibiting heroic acts of saving other people, demonstrating various acts of kindness, giving of an unprecedented amount of generosity and goodwill, and other behaviors that are considered virtuous, pure, or even "superhuman." This positive emotion is called elevation and is characterized by physical feelings in one's chest of a distinct sensation of warmth, pleasantness, or "tingling" feelings accompanied by the desire to help others, to become a better person, or to affiliate with others (Haidt, 2003). Again, if you can go out of your house, go to your nearest kitchen soup, homeless shelter or outreach centers of charitable organizations and observe how they take care of exposed, at-risk and vulnerable people in this time of crisis. You can also watch thousands of YouTube videos of people helping other people, but I must be honest, seeing it physically with your own eyes is an experience worth having. Sometimes it takes the worst of the human condition to bring out the best of humanity.

Psychological capital (PsyCap). A psychological construct composed of four psychological resources of Hope, Efficacy, ResilienceandOptimism or as Luthans & Youssef (2004) fondly coined as "The HERO Within." Hope is the perceived capability to seek and find pathways to reach desired goals, and motivate oneself via self-agency (autonomy to think and act) to use those pathways (Snyder, 2002) while Efficacy (or self-efficacy) is the belief and confidence in one's abilities to achieve desired goals. On the other hand, Resilience is the capacity for positive adaptation in significant adversity (Cutuli et al., 2018) and Optimism as a mood or attitude associated with the expectation of a desirable, advantageous, or pleasurable future (Peterson, 2006). Think of PsyCap as taking multivitamins in that if you use them all together, you are in a better and more prepared position to take any crisis head-on, including Covid-19. Recent news seems to indicate that there are already some hopeful signs that a treatment or vaccine is in the making; people are self-quarantining themselves since by doing so, it can help cut the transmission of the virus (i.e., self-efficacy); survivors of the virus report a more positive appreciation of life (i.e., resilience); and, people and the world believe that the outbreak will be eventually contained and we will live in a better "new normal" as we learn from this experience and use that learning to create a better way of working, relating with others, and taking care of our environment.

Meaning-making. Amidst all these chaos, uncertainty and fear, what do all of these mean? If you have asked this question during this period, you are now doing what psychology calls meaning-making, and that is a good thing to do. Meaning-making is the process of how people interpret, understand or make sense of life events, relationships and even one's self. To facilitate meaning-making, Steger (2018) suggests three ways: recognize your significance (one’s life has value or worth living), define your purpose (mission in life), and comprehend the situation or make sense of your experience of this pandemic. Perhaps, a positive outcome of this pandemic is that more people would have gained a better understanding of themselves, their reason for being (ikigai), or their life's purpose so that they can live more meaningful and purpose-driven lives.

The important thing is that you start practicing what I call Positive Distancing, the marriage of social distancing, and mental-emotional distancing to address the paradoxical needs of the collective (social) and individuals (mental-emotional).

Meanwhile, be safe and stay safe.

Suggested Readings:

Is Greta a Transformational Leader?

Vital Engagement: When Meaning Meets Flow

Flow: The psychology of optimal experience

On Finding Meaning in Life and at Work

Positive HR: Positively Reinventing HR

References

Brower, T. (17 March 2020). Coronavirus Creating Stress? Why you may need mental distancing as much as social distancing and 8 ways to get it. Forbes. Retrieved 19 March 2020 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/tracybrower/2020/03/17/stressed-because-of-the-coronavirus-why-you-need-mental-distancing-as-much-as-social-distancing-and-8-ways-to-get-it/#25b9e7fedbbe

Bryant, F., & Veroff, J. (2007). Savoring. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Chapters 1 & 8 (“Concepts of Savoring: An Introduction” & “Enhancing Savoring,” pp. 1-24 & 98-215).

Cutuli, J., Herbers, J., Masten, A., & Reed, M. (2018). Resilience in development. In C.R. Snyder, S. Lopez, L.M. Edwards, & S.C. Marques (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Row.

Gross, J., & John, O. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), p. 348-362.

Haidt, J. (2003). Elevation and the positive psychology of morality. In C. L. M. Keyes & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived (pp. 275-289). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Johnson, C., Sun, L. & Freedman, A. (10 March 2020). Social distancing could buy U.S. valuable time against coronavirus. The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 March 2020, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/03/10/social-distancing-coronavirus/.

Luthans F., & Youssef, C.M. (2004). Human, social, and now positive psychological capital management: Investing in people for competitive advantage, Organizational Dynamics, 33(2), 143-160.

Peterson, C. (2006). A primer in positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Porta, M., & International Epidemiological Association. (2008). A dictionary of epidemiology (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. (2008).

Riley K. (2013) Benefit Finding. In: Gellman M.D., Turner J.R. (eds) Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. Springer, New York, NY

Snyder, C. (2002). Hope Theory: Rainbows in the Mind. Psychological Inquiry,13(4), 249-275. Retrieved March 19, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/1448867.

Specktor, B. (16 March 2020). Coronavirus: What is 'flattening the curve,' and will it work? LiveScience. Retrieved 19 March 2020 from https://www.livescience.com/coronavirus-flatten-the-curve.html.

Steger, M. (2018). Meaning in life: A unified model. In C.R. Snyder, S.J. Lopez, L.M. Edwards, & S.C. Marques (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (3rd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Teasdale, J., Williams, M., and Segal, Z. (2014), The mindful way workbook: An 8-week program to free yourself from depression and emotional distress. New York, NY: Guilford.

Walsh, R., & Shapiro, S.L. (2006). The meeting of meditative disciplines and Western psychology: A mutually enriching dialogue. American Psychologist, 61, 227-239.

Wiles, S. (19 March 2020). The three phases of Covid-19 and how we can make it manageable. The Spinoff. Retrieved 19 March 2020 from https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/09-03-2020/the-three-phases-of-covid-19-and-how-we-can-make-it-manageable/.***

|

|

|

TELL US WHAT YOU THINK: